Great (Genre) Expectations

I've been thinking about genre a bit lately. Well, it's more accurate to say that I've been thinking about genre pretty regularly for the past twenty-odd years, ever since taking a single class on film genres in my senior year of college. In any case, last week I was listening to David Naimon's conversation with Vajra Chandrasekera, in which they discussed both Chandrasekera's first novel, The Saint of Bright Doors, and his second, Rakesfall. As in every episode of Between the Covers, the conversation was wide-ranging and thought-provoking, just excellent all around. But the part that has stuck most in my mind was this part toward the beginning:

David Naimon: I want to spend some time exploring some of the questions your first book raises as a way to prepare us to discuss Rakesfall, especially because some of the things that are true about your first book are an order of magnitude more true about your second. Saints was mainly met with thunderous critical acclaim but also at the same time, with a much smaller number of equally passionate people who were dissenters with the book, a recent focus for instance on a popular podcast that roasts books, what these two camps have in common is a sense of, “What the f*ck” or “What is this?” The larger group is thrilled by this experience. The smaller group is put off by it.

The Saint of Bright Doors is, I would say, recognizably a part of the fantasy genre insofar as it is set in a second world where magic and magical creatures exist. It is also shelved as fantasy in bookstores and libraries, and was published by Tor, a publisher known for speculative fiction. Yet a reader who is well-versed in mainstream American fantasy fiction would, as David noted, likely find this book confusing in that it doesn't do what fantasy novels usually do. For one example, consider: in the opening of the book we are presented with the main character, Fetter, who is raised by his mother to be the perfect assassin to kill his father, a messianic figure in one of the religions of the book's world. In a typical fantasy, this sort of setup would lead directly into a hero narrative in which Fetter learns his craft as an assassin and goes on a quest to find and slay his father, culminating in some sort of battle (literal or figurative) between father and son.

But this isn't what happens in The Saint of Bright Doors. Instead, within the first chapter or so, Fetter rejects his mission, moves to the city, and joins a support group for cast-off Chosen Ones. It's clear that this is at least in part because Chandrasekera is deliberately subverting genre expectations. And, as David noted, readers have found that subversion either delightful or frustrating. That different readers will respond differently to the same text is, of course, about as surprising as water being wet, but I'm particularly interested in looking at how genre functions in terms of our understanding of a text.

I occasionally try to talk about genre on social media but often find myself frustrated by the fact that most of the responses I get—when I get any responses at all—take a prescriptive approach to genre. People will talk about where a book would (or should be) shelved. People will talk about genre as a set of rules to be followed. And people will frequently describe the quality of a book in terms of how closely it follows those rules—a good book is one that follows its genre rules, a bad book is one that does not. But however much my probably-autistic brain enjoys pattern-finding and categorization, this kind of discourse around genre is my least favorite and the least interesting to me.

Let me throw out a few ideas that are fairly standard and not at all new in academic discussions of genre (certainly they were not new ideas when they were presented to me in that film studies class 23 years ago):

- Genre is an emergent property of literature. It is a conversation between texts, readers, and writers. Any time audiences and authors are aware of more than one text, comparisons and contrasts are going to be made between texts and patterns are going to be noticed. And once the patterns are noticed, authors are going to generate new texts that incorporate an awareness of those patterns. This is the process by which genres arise, are propagated, and are utilized by authors and audiences.

- Genre definitions are always going to be imprecise because they arise out of the texts that make up the body of the genre, rather than being imposed from the top-down by some sort of authority figure. Because there is no central authority, each reader and each author has to negotiate between our own understanding of a genre and everyone else's understanding of it. In that way, it's a lot like most other forms of communication.

- Because genre definitions are imprecise and decentralized, the boundaries of every genre is going to be fuzzy. What that means is that while there are always going to be many works that are completely non-controversially included as part of a genre—The Lord of the Rings as fantasy, for example, or the Sherlock Holmes stories as mysteries—there are also always going to be many works where it's unclear or at least non-unanimous whether they should be included in a genre.

- A single work of art can meaningfully be a part of more than one genre. Not only does that mean that one book can include tropes and structures from multiple genres, but it also means that we can analyze and understand a single book from multiple genre angles at the same time.

- No single text ever incorporates every trope or structure or characteristic of a given genre. That doesn't prevent it from participating in that genre.

- Because human brains look for patterns, a major way that genres operate is by creating expectations in the audience. Whether a given text upholds or subverts its genre's expectations—or, rather, which expectations it upholds and which it subverts—is a valuable key to its meaning.

If we let go of the idea of genre as a set of rules and instead use it as an interpretive lens, so much can be opened up! Consider: once upon a time, I tried to have an open-ended conversation on social media about genre, and one person who responded to me brought up the example of Star Wars, and how it would be ridiculous to consider Star Wars a Western. The ironic thing is that among the reading I was assigned for that film genres class I mentioned above was an essay all about analyzing Star Wars as a Western! Sure, you can point out that Star Wars doesn't take place in the American West. There aren't literal cowboys or horses or six-shooters. But a lot of the iconography of especially A New Hope is clearly drawn from Westerns, as are many aspects of the plot structure. Rather than saying "Star Wars is not a Western"—which simply ends the conversation—if we say that Star Wars is a Western, it allows us to take all of the analysis and discussion around a century of Western film and literature and apply those to our understanding of this other work. We can ask questions like "Why would an ostensibly science fiction movie choose to uphold these tropes of the Western genre, and what meaning can we draw from that?" And if Star Wars isn't your thing, you can ask these same kinds of questions about any text that participates in a genre, which is to say any text at all.

Now, I do think that at least part of what many people were responding to with The Saint of Bright Doors was about novelty. Certainly I had never read a book like that before, and when you read a lot, sameness can get boring. In that case, something new can often be something exciting.

On the other hand, lots of people also read to be comforted or to be entertained in familiar ways, in which case novelty may not be welcome except within certain boundaries. And, to be clear, there's nothing wrong with that. People can read however they want, toward whatever end they want. And people have lots of opportunity to read that way if they want to. I often want to read that way. I often do read that way.

But, for me at least, those comforting, familiar genre reads are often not the ones that I find interesting to talk about. I'm glad they're there when I want them. But when I really want to dig into a conversation about a book, I'm glad that there are books that challenge genre expectations, too.

If I were a smarter reader, I'd probably launch here into a discussion about the ways that The Saint of Bright Doors subverts genre and why and what it means. Alas, I am not equipped to write that essay. Not yet, anyway. If you're interested in that conversation, David's episode with Chandrasekera is a good place to start. Let me know how it goes!

Putting the Photo In a Different Section So You Don't Think It's Connected to the Text

What I've Been Working On

Keep the Channel Open

Jennifer Baker has been one of the people I've looked up to for a while as a model of literary citizenship, so when I heard that she had a YA novel coming out, I immediately pre-ordered it. Forgive Me Not is a powerful and insightful book about the American carceral system, as well as a moving coming-of-age and family story.

The story follows Violetta Chen-Samuels, a high school student in New York City whose life has gone off the rails, culminating in the death of her younger sister in a drunk driving accident that Violetta caused. In this version of New York, juvenile offenders are given the option of enduring Trials—a sort of codified form of "tough love"—instead of incarceration. But despite being intended as a reform of the criminal justice system, the Trials, too, are harsh and retributive. Forgive Me Not delves into the harms of our carceral system, and how race, class, gender, and other systems of marginalization interact with it, and ultimately the question of forgiveness and punishment.

Jennifer and I had a great conversation about how she approached writing her characters, why it was important for her to focus on systems rather than individual guilt or innocence, and how to write about serious topics for younger readers.

Hey, It's Me

Rachel and I are trying to commit to a two-episode-per-month schedule for Hey, It's Me, and so far it's going pretty well. For our first episode in August, I asked to talk about Star Trek, and particularly what it was about the more recent series that didn't really feel like Star Trek to me, even though I have been enjoying them. As always, we wandered a bit far afield from that premise, to conversational spots including Star Trek as personal foundational text, cozy fiction, optimism vs. hope, and the cultural role of motherhood.

For our second episode, Rachel sent me the first section of her novel-in-progress so that we could discuss it. If you've been listening along, you'll have heard us mention the novel a few times before, but one piece of context that might not have gotten mentioned is that the book's main character is named Rachel Zucker, and another major character is named Mike and talks exactly like me. As many of our episodes do, this one does get a bit meta. But I think that there's also some really interesting discussion about the art-making process, not to mention that the dynamic between two friends trying to talk around and into a sort of challenging topic. I am really interested to know how this episode in particular strikes listeners.

What I've Been Reading

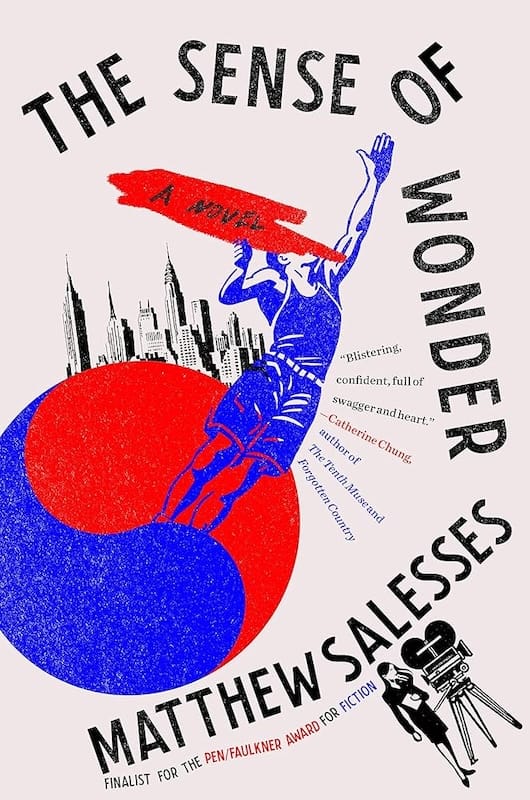

Featured Read: The Sense of Wonder, by Matthew Salesses

Not too far into the second section of Matthew Salesses's latest novel, The Sense of Wonder, Carrie Kang—a Korean American K-drama producer—explains to the reader that "Unlike in Hollywood, in Korea, plot happens because of who people are, not because of what they choose." Added together with the book's opening, in which the other main character—Won Lee, the only Asian American player in the NBA—recounts a racist joke about an Asian American basketball player, I think you have a key to understanding what this story is about.

The Sense of Wonder is very much inspired by Jeremy Lin's rise and fall in the NBA, something that Salesses wrote about back in 2012, just before Lin's season was ended due to injury. Here, instead of "Linsanity," Won's sudden success is dubbed "the Wonder," but the parallels are clear. We also see the ways that K-drama informs the book via Carrie's sections and the romantic relationship between Won and Carrie.

I'd previously read Salesses's novel Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear (and spoke with him about the book on Keep the Channel Open), a book that I loved for its strangeness and the way it literalizes the "split subject" phenomenon of Asian Americanness. I also loved this one, but where Doppelgänger felt experimental and often unsettling, Wonder feels more straightforward. Don't mistake me: this book is intelligent and incisive and complex in its commentary on race, relationships, culture, family. It's moving and resonant in how it presents its characters. It's funny and tragic and redemptive. But the text is also accessible and propulsive in a way that had me rocketing through the book in just a couple of sittings. I don't know that I could say which book is better, just that the experience of reading them was very different, and that I thought both were excellent.

Have you read this one? I'd love to hear what you thought of it if you have. And if you haven't, here are some purchase links:

Everything Else

- Hydra Medusa, by Brandon Shimoda. I have to admit, this one was a little beyond me. I think that the poems here are largely about mortality and dreams and memory, and there is a dream-like quality to them that was evocative. But I just have a lot of difficulty when it comes to language-forward poetry, and mostly I just found myself feeling confused. To be clear, I think this is a deficiency on my part, not really on the part of the poems.

- A Living Remedy, by Nicole Chung. I think what Nicole Chung does here in terms of portraying the landscape of grief is very moving, and very familiar to my experience of different kinds of grief. Beautifully written, and a beautiful testament to her and her parents' love.

- Firebreak, by Nicole Kornher-Stace. There’s a brightness at the core of this one that belies the bleakness of the cyberpunk-style megacorp dystopian setting, I think. Fast-paced and very enjoyable, with an anti-capitalist theme that I expect will work well for a lot of people.

- The Tatami Galaxy, by Tomihiko Morimi. I picked this one up on a whim when I was at a local bookstore for a reading a few months back. I didn't know at the time that it was written by the same author as The Night Is Short, Walk on Girl, nor that it had an anime adaptation by Masaaki Yuasa. It's an interesting and often very funny parallel worlds story, showing the same stretch of the unnamed narrator's junior year of college if he had made different choices as a freshman. The narrator's voice is very well realized, which did provide a bit of friction for me as a reader since he is self-absorbed, often self-deluding, and just generally kind of obnoxious and cringy—much in the same way that I was obnoxious and cringy at 20. But in the end it winds up being a satisfying read, for me, at least.

Mattered To Me

- Something I appreciate so much about the sort of writing advice that Alexander Chee gives is that it is always so concrete and actionable, that it is gives a look at what it means to be a writer on both a practical and a philosophical level. In a recent newsletter, he wrote about making community, balancing writing with a day job, and gave some advice about how to get a feel for the literary landscape you're trying to become a part of.

- Helena Fitzgerald wrote about pizza in the sitcoms of the '90s and early '00s, and it's such a great example of what she does best as a writer, I think. It also made me want quite a lot to eat a pizza.

- The first segment of last week's episode of the BBC podcast Short Cuts—a segment entitled "Autism Plays Itself"—presents an audio description of a medical film from the 1950s that documented the movements and behavior of children with autism, along with the reactions of three autistic adults watching the film in present day. The gentleness and understanding of the watcher's responses were so moving to me, and articulated something about the experience of autism that I hadn't ever really put into words before. I still don't know if I'm actually autistic, but there was still something about this segment that made me feel seen in a way that got me a bit emotional.

Tell me something good. If you have a minute, I mean.

-Mike